世界百大品牌 – Rank no.74 – US

Top 100 Brand in The World – Rank no.74 – VISA – US

|

|

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Traded as | NYSE: V Dow Jones Industrial Average Component S&P 500 Component |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | Fresno, California, U.S. (1958)as BankAmericard |

| Headquarters | Foster City, California[1], U.S. |

| Area served | Worldwide |

| Key people | Joseph Saunders (Executive Chairman) Charles Scharf (CEO) Ryan McInerney (President) |

| Products | Credit cards, payment systems |

| Revenue | |

| Operating income | |

| Net income | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Employees | 8,500 (2012)[2] |

| Website | visa.com |

Visa Inc. (/ˈviːzə/ or /viːsə/) is an American multinational financial services corporation headquartered in Foster City, California, United States. It facilitates electronic funds transfers throughout the world, most commonly through Visa-branded credit cards anddebit cards.[3] Visa does not issue cards, extend credit or set rates and fees for consumers; rather, Visa provides financial institutions with Visa-branded payment products that they then use to offer credit, debit, prepaid and cash-access programs to their customers. In 2008, according to The Nilson Report, Visa held a 38.3% market share of the credit card marketplace and 60.7% of the debit card marketplace in the United States.[4] In 2009, Visa’s global network (known as VisaNet) processed 62 billion transactions with a total volume of $4.4 trillion.[5][6]

Visa has operations across Asia-Pacific, North America, Central and South America, the Caribbean, Western Europe, Central andEastern Europe, Africa and Middle East. Visa Europe is a separate membership entity that is an exclusive licensee of Visa Inc.’s trademarks and technology in the European region, issuing cards such as Visa Debit.

History[edit]

In mid-September 1958, Bank of America (BofA) launched its BankAmericard credit card program in Fresno, California, with an initial mailing of 60,000 unsolicited credit cards.[7] The original idea was the brainchild of BofA’s in-house product development think tank, the Customer Services Research Group, and its leader, Joseph P. Williams. Williams convinced senior BofA executives in 1956 to let him pursue what became the world’s first successful mass mailing of unsolicited credit cards (that is actual working cards, not mere applications) to a large population.[8]

Williams’ accomplishment was in the successful implementation of the all-purpose credit card, not in coming up with the idea.[9] By the mid-1950s, the typical middle-class American already maintained revolving credit accounts with several different merchants, which was clearly inefficient and inconvenient due to the need to carry so many cards and pay so many separate bills each month.[10] The need for a unified financial instrument was already palpably obvious to the American financial services industry, but no one could figure out how to do it. There were already charge cards like Diners Club (which had to be paid in full at the end of each billing cycle), and “by the mid-1950s, there had been at least a dozen attempts to create an all-purpose credit card.”[10] However, these prior attempts had been carried out by small banks which lacked the resources to make them work.[10] Williams and his team studied these failures carefully and believed they could avoid replicating those banks’ mistakes; they also studied existing revolving credit operations at Sears and Mobil Oil to learn why they were successful.[11] Fresno was selected for its population of 250,000 (big enough to make a credit card work, small enough to control initial startup cost), BofA’s market share of that population (45%), and relative isolation, to control public relations damage in case the project failed.[12]

The 1958 test at first went smoothly, but then BofA panicked when it confirmed rumors that another bank was about to initiate its own drop in San Francisco, BofA’s home market.[13] By March 1959, drops began in San Francisco and Sacramento; by June, BofA was dropping cards in Los Angeles; by October, the entire state had been saturated with over 2 million credit cards, and BankAmericard was being accepted by 20,000 merchants.[14] However, the program was riddled with problems, as Williams (who had never worked in a bank’s loan department) had been too earnest and trusting in his belief in the basic goodness of the bank’s customers, and he resigned in December 1959.[15] Twenty-two percent of accounts were delinquent, not the 4% expected, and police departments around the state were confronted by numerous incidents of the brand new crime of credit card fraud.[16] Both politicians and journalists joined the general uproar against Bank of America and its newfangled credit card, especially when it was pointed out that the cardholder agreement held customers liable for all charges, even those resulting from fraud.[17] BofA officially lost over $8.8 million on the launch of BankAmericard, but when the full cost of advertising and overhead was included, the bank’s actual loss was probably around $20 million.[17]

However, after purging Williams and his protégés, BofA management realized that BankAmericard was salvageable.[18] They conducted a “massive effort” to clean up after Williams, imposed proper financial controls, published an open letter to 3 million households across the state apologizing for the mess they had caused, and eventually were able to make the new financial instrument work.[19]

The original goal of BofA was to offer the BankAmericard product across California, but in 1965, BofA began to sign licensing agreements with a group of banks outside of California. BofA itself (like all other U.S. banks at the time) could not expand directly into other states due to federal restrictions not repealed until 1994. Over the following 11 years, various banks licensed the card system from Bank of America, thus forming a network of banks backing the BankAmericard system across the United States.[20] The “drops” of unsolicited credit cards continued unabated, thanks to BofA and its licensees and competitors, until they were outlawed in 1970[21] due to the serious financial chaos they caused, but not before over 100 million credit cards had been distributed into the American population.[22]

During the late 1960s, BofA also licensed the BankAmericard program to banks in several other countries, which began issuing cards with localized brand names. For example:[citation needed]

- In Canada, an alliance of banks (including Toronto-Dominion Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Royal Bank of Canada,Banque Canadienne Nationale and Bank of Nova Scotia) issued credit cards under the Chargex name from 1968 to 1977.

- In France, it was known as Carte Bleue (Blue Card). The logo still appears on many French-issued Visa cards today.

- In the UK, the only BankAmericard issuer for some years was Barclaycard.

In 1970, the Bank of America gave up control of the BankAmericard program.[citation needed] The various BankAmericard issuer banks took control of the program, creating National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI), an independent non-stock corporation which would be in charge of managing, promoting and developing the BankAmericard system within the United States, although Bank of America continued to issue and support the international licenses themselves. By 1972, licenses had been granted in 15 countries. In 1974, IBANCO, a multinational member corporation, was founded in order to manage the international BankAmericard program.[citation needed]

|

|

|

|

Sample Barclaycard (left), as issued in the UK in the 1960s/70s. Co-branded cards were also issued by affiliates, such as the Co-operative Bank and Yorkshire Bank. The Chargex logo (right) used in Canada, along with the names of the 5 Canadian federal banks that issued Chargex cards.

|

||

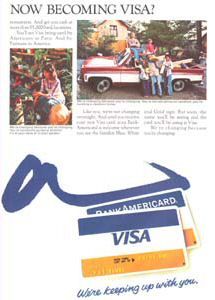

In 1976, the directors of IBANCO determined that bringing the various international networks together into a single network with a single name internationally would be in the best interests of the corporation; however in many countries, there was still reluctance to issue a card associated with Bank of America, even though the association was entirely nominal in nature. For this reason, in 1975 BankAmericard, Chargex, Barclaycard, Carte Bleue, and all other licensees united under the new name, “Visa”, which retained the distinctive blue, white and gold flag. NBI became Visa USA and IBANCO became Visa International.[citation needed]

The term Visa was conceived by the company’s founder, Dee Hock. He believed that the word was instantly recognizable in many languages in many countries, and that it also denoted universal acceptance.[citation needed] Nowadays, the termVisa has become a recursive backronym for Visa International Service Association.[23]

In October 2007, Bank of America announced it was resurrecting the BankAmericard brand name as the “BankAmericard Rewards Visa”.[24]

Corporate structure[edit]

Prior to October 3, 2007, Visa comprised four non-stock, separately incorporated companies that employed 6000 people worldwide: Visa International Service Association (Visa), the worldwide parent entity, Visa U.S.A. Inc., Visa Canada Association, and Visa Europe Ltd. The latter three separately incorporated regions had the status of group members of Visa International Service Association. The unincorporated regions (Visa Latin America (LAC), Visa Asia Pacific and Visa Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa (CEMEA) were divisions within Visa.

Billing & finance charge methods[edit]

Initially, signed copies of sales drafts were included in each customer’s monthly billing statement for verification purposes—an industry practice known as “Country Club Billing”. By the late 1970s, however, billing statements no longer contained these enclosures, but rather a summary statement showing posting date, purchase date, reference number, merchant name, and the dollar amount of each purchase. At the same time, many issuers, particularly Bank of America, were in the process of changing their methods of finance charge calculation. Initially, a “previous balance” method was used—calculation of finance charge on the unpaid balance shown on the prior month’s statement. Later, it was decided to use “average daily balance” which resulted in increased revenue for the issuers by calculating the number of days each purchase was included on the prior month’s statement. Several years later, “new average daily balance”—in which transactions from previous AND current billing cycles were used in the calculation—was introduced. By the early 1980s, many issuers introduced the concept of the annual fee as yet another revenue enhancer. Today, many cards are co-branded with various merchants, airlines, etc. and marketed as “reward cards”.

IPO and restructuring[edit]

On October 11, 2006, Visa announced that some of its businesses would be merged and become a publicly traded company, Visa Inc.[25][26][27] Under the IPO restructuring, Visa Canada, Visa International, and Visa U.S.A. were merged into the new public company. Visa’s Western Europe operation became a separate company, owned by its member banks who will also have a minority stake in Visa Inc.[28] In total, more than 35 investment banks participated in the deal in several capacities, most notably as underwriters.

On October 3, 2007, Visa completed its corporate restructuring with the formation of Visa Inc. The new company was the first step towards Visa’s IPO.[29] The second step came on November 9, 2007, when the new Visa Inc. submitted its $10 billion IPO filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[30] On February 25, 2008, Visa announced it would go ahead with an IPO of half its shares.[31] The IPO took place on March 18, 2008. Visa sold 406 million shares at US$44 per share ($2 above the high end of the expected $37–42 pricing range), raising US$17.9 billion in the largest initial public offering in U.S. history.[32] On March 20, 2008, the IPO underwriters (including JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs & Co., Banc of America Securities LLC, Citi, HSBC, Merrill Lynch & Co., UBS Investment Bank and Wachovia Securities) exercised their overallotment option, purchasing an additional 40.6 million shares, bringing Visa’s total IPO share count to 446.6 million, and bringing the total proceeds to US$19.1 billion.[33] Visa now trades under theticker symbol “V” on the New York Stock Exchange.[34]

Criticism and controversy[edit]

WikiLeaks[edit]

Visa Europe began suspending payments to WikiLeaks on 7 December 2010.[35] The company “said it was awaiting an investigation into ‘the nature of its business and whether it contravenes Visa operating rules’ – though it did not go into details”.[36] In return Datacell, the IT company that enables WikiLeaks to accept credit and debit card donations, announced that it will take legal action against Visa Europe.[37] On December 8, the group Anonymous performed a DDoS attack on visa.com[clarification needed], bringing the site down.[38] Although “the Norway-based financial services company Teller AS, which Visa ordered to look into WikiLeaks and its fundraising body, the Sunshine Press, found no proof of any wrongdoing, Visa Europe announced in January 2011 that “it would continue blocking donations to the secret-spilling site until it completes its own investigation”.[36]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated that Visa may be “violating WikiLeaks’ right to freedom of expression” by withdrawing their services.[39]

The Icelandic judiciary decided that Valitor (company related to Visa and MasterCard) was violating the law when it prevented donation to the site by credit card. A justice ruled that the donations will be allowed to return to the site after 14 days or they would be fined in the amount of U$ 6,000.[40]

Litigation and regulatory actions[edit]

Anti-trust lawsuit by ATM operators[edit]

MasterCard, along with Visa, has been sued in a class action by ATM operators that claims the credit card networks’ rules effectively fix ATM access fees. The suit claims that this is a restraint on trade in violation of federal law. The lawsuit was filed by the National ATM Council and independent operators of automated teller machines. More specifically, it is alleged that MasterCard’s and Visa’s network rules prohibit ATM operators from offering lower prices for transactions over PIN-debit networks that are not affiliated with Visa or MasterCard. The suit says that this price fixing artificially raises the price that consumers pay using ATMs, limits the revenue that ATM-operators earn, and violates the Sherman Act’s prohibition against unreasonable restraints of trade. Johnathan Rubin, an attorney for the plaintiffs said, “Visa and MasterCard are the ringleaders, organizers, and enforcers of a conspiracy among U.S. banks to fix the price of ATM access fees in order to keep the competition at bay.” [41]

Debit card swipe fees[edit]

Visa Inc.’s headquarters in Foster City,California, is home to a significant portion of the company’s operations.

Visa settled a 1996 antitrust lawsuit brought by a class of U.S. merchants, including Wal-Mart, for billions of dollars in 2003. Over 4 million class members were represented by the plaintiffs. According to a website associated with the suit,[42] Visa and MasterCardsettled the plaintiffs’ claims for a total of $3.05 billion. Visa’s share of this settlement is reported to have been the larger.

U.S. Justice Department actions[edit]

In October 2010, Visa and MasterCard reached a settlement with the U.S. Justice Department in another antitrust case. The companies agreed to allow merchants displaying their logos to decline certain types of cards (because interchange fees differ), or to offer consumers discounts for using cheaper cards.[43]

In 1998 the Department of Justice sued Visa over rules prohibiting its issuing banks from doing business with American Express andDiscover. The Department of Justice won its case at trial in 2001 and the verdict was upheld on appeal. American Express and Discover filed suit as well.[44]

Anti-trust issues in Europe[edit]

In 2002 the European Commission exempted Visa’s multilateral interchange fees from Article 81 of the EC Treaty that prohibits anti-competitive arrangements.[45] However, this exemption has expired on December 31, 2007. In the United Kingdom, MasterCard has reduced its interchange fees while it is under investigation by the Office of Fair Trading.

In January 2007, the European Commission issued the results of a two-year inquiry into the retail banking sector. The report focuses on payment cards and interchange fees. Upon publishing the report, Commissioner Neelie Kroes said the “present level of interchange fees in many of the schemes we have examined does not seem justified.” The report called for further study of the issue.[46]

On March 26, 2008, the European Commission opened an investigation into Visa’s multilateral interchange fees for cross-border transactions within the EEA as well as into the “Honor All Cards” rule (under which merchants are required to accept all valid Visa-branded cards).[47]

The antitrust authorities of EU Member States other than the United Kingdom are also investigating MasterCard’s and Visa’s interchange fees. For example, on January 4, 2007, the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection fined twenty banks a total of PLN 164 million (about $56 million) for jointly setting MasterCard’s and Visa’s interchange fees.[48]

In December 2010, Visa reached a settlement with the European Union in yet another antitrust case, promising to reduce debit card payments to 0.2 percent of a purchase.[49] A senior official from the European Central Bank called for a break-up of the Visa/MasterCard duopoly by creation of a new European debit card for use in the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA).[50] After Visa’s blocking of payments to WikiLeaks, members of the European Parliament expressed concern that payments from European citizens to a European corporation could apparently be blocked by the US, and called for a further reduction in the dominance of Visa and MasterCard in the European payment system.[51]

Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant Discount Antitrust Litigation[edit]

On 27 November 2012, a federal judge entered an order granting preliminary approval to a proposed settlement to a class-action lawsuit filed in 2005 by merchants and trade associations against Visa, MasterCard, and many credit card issuing banks. The suit was filed due to price fixing and other anti-competitive trade practices employed by MasterCard and Visa. A majority of named-class plaintiffs have objected and vowed to opt out of the settlement. Opponents object to provisions that would bar future lawsuits and even prevent merchants from opting out of significant portions of the proposed settlement. Stephen Neuwirth, a lawyer representing Home Depot, said, “It’s so obvious Visa and MasterCard were prepared to make a large payment because of the scope of the releases being given. It’s all one quid pro quo and merchants like the Home Depot are being denied the chance to opt out of that quid pro quo and say this is a bad deal.” [52]

Plaintiffs allege that Visa, MasterCard, and major credit card issuers engaged in a conspiracy to fix interchange fees, also known as swipe fees, that are charged to merchants for the privilege of accepting payment cards at artificially high levels. In their complaint, the plaintiffs also alleged that the defendants unfairly interfere with merchants from encouraging customers to use less expensive forms of payment such as lower-cost cards, cash, and checks.[52]

The settlement provides for the cash equivalent of a 10 basis-point reduction (0.1 percent) of swipe fees charged to merchants for a period of eight months. This eight-month period would probably begin in the middle of 2013. The total value of the settlement will be about $7.25 billion.[52] According to court filings, Target, Wal-Mart, Home Depot, Neiman Marcus, Saks, and 1,200 other plaintiffs oppose the settlement. A group of large merchants including Kroger, Walgreens, and Safeway have reached a separate agreement with the defendants over swipe fees.[52] The NACS, for example, harshly criticised the settlement and is urging its members to opt-out.

Tom Robinson, chairman of NACS and president of Robinson Oil, said, “This proposed settlement allows the card companies to continue to dictate the prices banks charge and the rules that constrain the market including for emerging payment methods, particularly mobile payments. Consumers and merchants ultimately will pay more as a result of this agreement — without any relief in sight.” [53] Josh Floum, general counsel for Visa, responded, “Our belief that the agreement will eventually receive final approval was strengthened today. As we have said from the beginning, this settlement is a fair and reasonable compromise for all parties.” [52]

In January 2013, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that any appeals against the settlement that received preliminary approval in November 2012 would not be heard until objections to the settlement are filed and considered by the trial court in September 2013. The practical effect of this ruling was to allow settlement notices to be sent to eligible merchants.[54]

High swipe fees in Poland[edit]

Very high interchange fee for Visa (1,5%-1,6% from every transaction final price, which include also VAT tax) in Poland started discussion about legality and need for government regulations of interchange fee to avoid high cost for business (which also block electronic payment market and acceptability of cards).[55] This situation also lead to the birth of new methods of payments, which avoid need for go-between (middleman) companies like Visa or MasterCard, for example mobile application issued by major bank.,[56] and system by big chain of discount shops.[57] or older public transport tickets buying systems.[58]

Corporate affairs[edit]

Headquarters[edit]

As of October 1, 2012, Visa’s headquarters are located in Foster City, California.[1] Visa had been headquartered in San Francisco until 1985, when it moved to San Mateo.[59]Around 1993, Visa began consolidating various scattered offices in San Mateo to a location in Foster City.[59] Visa became Foster City’s largest employer.

In 2009, Visa moved its corporate headquarters back to San Francisco when it leased the top three floors of the 595 Market Street office building, although most of its employees remained at its Foster City campus.[60] In 2012, Visa decided to consolidate its headquarters in Foster City where 3,100 of its 7,700 global workers are employed.[1] Visa owns four buildings at the intersection of Metro Center Boulevard and Vintage Park Drive.

On December 11, 2012 Visa Inc. confirmed that it will build a global information technology center off of the US 183 Expressway in northwest Austin, Texas.[61]

Operations[edit]

Visa offers through its issuing members the following types of cards:

- Debit cards (pay from a checking / savings account)

- Credit cards (pay monthly payments with or with out interest depending on a customer paying on time.)

- Prepaid cards (pay from a cash account that has no checkwriting privileges)

Visa operates the Plus automated teller machine network and the Interlink EFTPOS point-of-sale network, which facilitate the “debit” protocol used with debit cards and prepaid cards. They also provide commercial payment solutions for small businesses, midsize and large corporations, and governments.[62]

Operating regulations[edit]

Visa has a set of rules that govern the participation of financial institutions in its payment system. Acquiring banks are responsible for ensuring that their merchants comply with the rules.

Rules address how a cardholder must be identified for security, how transactions may be denied by the bank and how banks may cooperate for fraud prevention, and how to keep that identification and fraud protection standard and non-discriminatory. Other rules govern what creates an enforceable proof of authorization by the cardholder.[63]

The rules prohibit merchants from imposing a minimum or maximum purchase amount in order to accept a Visa card and from charging cardholders a fee for using a Visa card.[63]In ten U.S. states, surcharges for the use of a credit card are forbidden by law (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Oklahomaand Texas) but a discount for cash is permitted under specific rules.[64] Some countries have banned the no-surcharge rule, most notably the UK[65] and Australia[66] and retailers in those countries may apply surcharges to any credit-card transaction, Visa or otherwise.

Unlike MasterCard, Visa does permit merchants to ask for photo ID, although the merchant rule book states that this practice is “discouraged”. As long as the Visa card is signed, a merchant may not deny a transaction because a cardholder refuses to show a photo ID.[63]

The Dodd-Frank Act allows U.S. merchants to set a minimum purchase amount on credit card transactions, not to exceed $10.[67][68]

Recent complications include the addition of exceptions for non-signed purchases by telephone or on the Internet, and an additional security system called “Verified by Visa” for purchases on the Internet.

payWave[edit]

In September 2007, Visa introduced Visa payWave, a contactless payment technology feature that allows cardholders to wave their card in front of contact-less payment terminals without the need to physically swipe or insert the card into a point-of-sale device.[69] This is similar to the MasterCard PayPass service and the American Express ExpressPay, with both using RFID technology.

In Europe, Visa has introduced the V PAY card which is chip-only and PIN-only.[70]

Trade mark and design[edit]

Logo design[edit]

The blue and gold in Visa’s logo were originally chosen to represent the blue sky and golden-colored hills of California, where the legacy Bank of America was founded. The Visa symbol is used by merchants to denote the acceptance of Visa payment cards.

In 2006, Visa removed its trademark flag logo from all its cards, websites and retailer’s windows. This was the first time that Visa had changed its logo.[71] The new logo has a simple white background with the name Visa in blue with an orange flick on the ‘V’ (shown in the infobox at the top of this page).

For the new Visa Debit and Visa Electron logo, see the relevant pages.

Dove hologram[edit]

In 1984, most Visa cards around the world began to feature a hologram of a dove on its face, generally under the last four digits of the Visa number. This was implemented as a security feature – true holograms would appear 3-dimensional and the image would change as the card was turned. At the same time, the Visa logo, which had previously covered the whole card face, was reduced in size to a strip on the card’s right incorporating the hologram. This allowed issuing banks to customize the appearance of the card. Similar changes were implemented with MasterCard cards.

On older Visa cards, holding the face of the card under an ultraviolet light will reveal the dove picture, dubbed the Ultra-Sensitive Dove,[72] as an additional security test. (On newer Visa cards, the UV dove is replaced by a small V over the Visa logo.)

Beginning in 2005, the Visa standard was changed to allow for the hologram to be placed on the back of the card, or to be replaced with a holographic magnetic stripe (“HoloMag”).[73] The HoloMag card was shown to occasionally cause interference with card readers, so Visa eventually withdrew designs of HoloMag cards and reverted to traditional magnetic strips.[74][dead link]

Sponsorships[edit]

Olympics and Paralympics[edit]

- Visa has been a worldwide sponsor of the Olympic Games since 1980 and is the only card accepted at all Olympic venues. Its current contract with the International Olympic Committee and International Paralympic Committee (IP)] as the exclusive services sponsor will continue through 2020.[75] This includes the Singapore 2010 Youth Olympic Games, London 2012 Olympic Games, the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games, the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympic Games, the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, and the 2020 Olympic Games.

- Visa extended its partnership with the International Paralympic Committee through 2012, which includes the 2010 Vancouver Paralympic Winter Games and the 2012 London Paralympic Games. In 2002, Visa became the first global sponsor of the IPC.[76]

Others[edit]

- Visa is the shirt sponsor for the Argentina national rugby union team, nicknamed the Pumas. Also, Visa sponsors the Copa Libertadores and the Copa Sudamericana, the most important football club tournaments in South America.

- Until 2005, Visa was the exclusive sponsor of the Triple Crown thoroughbred tournament.

- Visa sponsored the Rugby World Cup, and the 2007 tournament in France was its last.[77]

- In 2007, Visa became sponsor of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The FIFA partnership provides Visa with global rights to a broad range of FIFA activities – including both the 2010 and 2014 FIFA World Cup and the FIFA Women’s World Cup.

- Since 1995, Visa has sponsored the U.S. NFL and a number of NFL teams, including the San Francisco 49ers whose practice jerseys display the Visa logo.[78] Visa’s sponsorship of the NFL currently extends through the 2014 season.[79]

- Starting from the 2012 season, Visa became a partner of the Caterham F1 Team. Visa is also known for motorsport sponsorship in the past, having previously sponsoredPacWest Racing‘s IndyCar team in 1995 and 1996, with drivers Danny Sullivan and Mark Blundell respectively.[80]