Real Estate Outlook 3/4

Inflation

From Disinflation to Reflation: A Reversal of Risks and Rewards

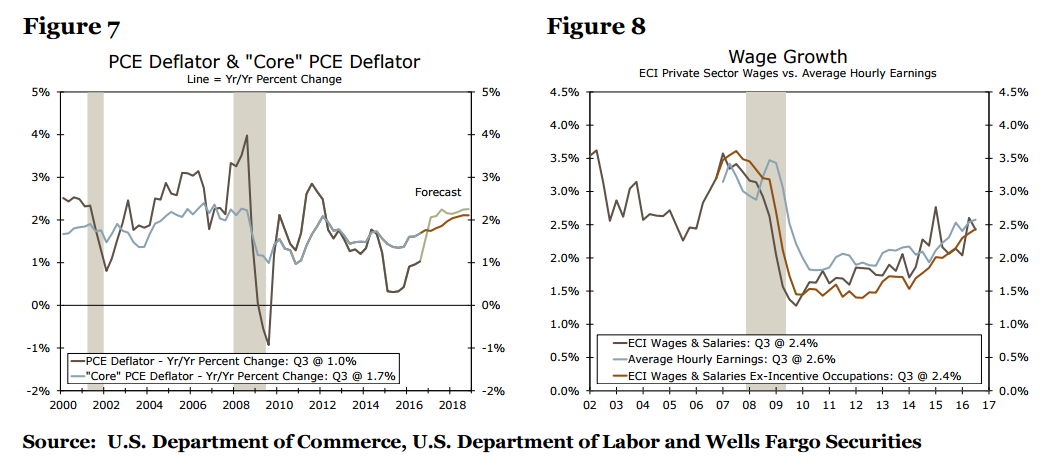

In recent years, the risks surrounding inflation have centered on the possibility of deflation in the U.S. and global economies. Lingering slack following the Great Recession, falling commodity prices and sharp strengthening in the dollar have kept core inflation below the Fed’s two percent target for all but a few months of the current expansion (Figure 7). The persistent shortfall between actual and targeted inflation had led policymakers and investors to believe that low inflation was the new status quo. With little risk of inflation running above the Fed’s target, there also looked to be little risk of the FOMC being forced to tighten faster than the gradual pace currently outlined by the Committee and market expectations. Yet, many of the headwinds of recent years are easing or, in some cases, reversing entirely. For decision makers, 2017 will be the year in which the Fed finally achieves reflation, but that success brings risks in its own right to real consumer spending, real returns on investments and the current path of monetary policy.

Broadening Sources of Higher Inflation

Within our framework for inflation, we factor in both short- and medium-term drivers, including commodity prices, the dollar and resource slack. As slack has continued to diminish, reflation in the U.S. economy has been delayed by deflation in the goods sector. Since 2014, declining commodity prices—first energy and more recently food prices—have been a drag on headline inflation, while the appreciation of the dollar has contributed to a decline in core consumer goods prices. Both of these drags, however, are easing. Oil prices have already rebounded about 50 percent off of the lows reached in early 2016 and prices are expected to climb further in 2017 as meaningful reductions in supply and demand growth north of one percent bring the market into balance around the middle of next year.

Core goods prices are likely to be less of a drag over the coming year. Although the dollar is anticipated to strengthen over 2017, as discussed in Section V on page 11, we expect the pace to be tame relative to the 2014-2015 period. Moreover, the dollar’s impact on import prices for consumer goods and, in turn, core consumer goods, lags by about one year. Therefore the weakening in the dollar since the start of 2016 should lead to a more modest drag on core consumer goods prices in 2017. The recent turnaround of producer price inflation in China, a proxy for global overcapacity pressures, is in positive territory for the first time since 2012, which also suggests a smaller drag from core consumer goods prices in the year ahead.

Perhaps the most important source of rising inflation in the year ahead will be continued tightening in the labor market. It has only been within the past year that the labor market has approached levels that could be considered full employment, making claims that the Phillips Curve—the relationship between the labor market and wages/inflation—is extinct somewhat premature. Wage growth has picked up over the past year by a range of measures (Figure 8). We expect employment costs to increase 2.6 percent in 2017.

While nominal wages are rising at the fastest pace of the expansion, labor productivity has continued to languish. As a result, unit labor costs have drifted higher and will likely put further pressure on company profit margins over the next year unless companies can pass on costs via higher selling prices.

Companies have thus far been hesitant to pass on higher costs. Profits as a share of GDP have fallen over the past two years, indicating compression in corporate margins. On the flip side, labor’s share of income has been rising, which suggests households are in a better position to tolerate a moderate rise in prices.

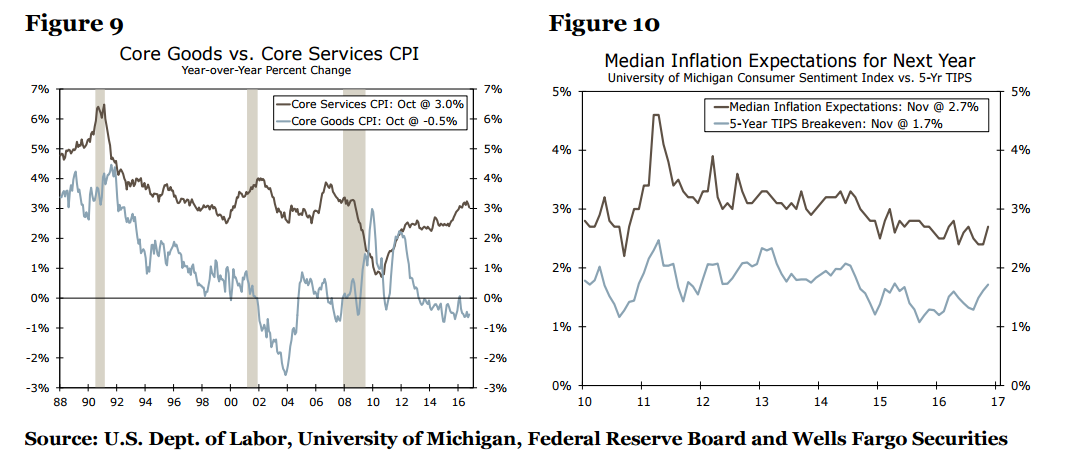

Rising wage pressures will be particularly important for the more labor-intensive service sector. Already core services inflation is rising above 3 percent when measured by the CPI (Figure 9). Over the past few years, rising shelter costs have been a key source of strength and an offset to disinflation in the also sizeable healthcare component. However, the trend for healthcare inflation has turned over the past year amid rising labor costs and increased usage. The turnaround will have greater bearing on the Fed’s preferred PCE measure, where healthcare has roughly a 20 percent weight. We expect core PCE inflation to rise to 2.2 percent in 2017. The strengthening in headline inflation is set to be even more pronounced amid the rebound in energy prices, with the PCE deflator rising 2.1 percent in 2017 compared to only an anticipated 1.1 percent this past year.

Are Consumers, Markets and the Fed Ready for Higher Inflation?

With price pressures building, the risk is no longer deflation, but whether households, businesses, investors and the Fed are prepared for rising inflation. Low inflation has been a key force behind the strength in real disposable income over the past year, but higher inflation will take a bigger bite out of household income growth in 2017. At present, consumers do not seem convinced that the trend in inflation is turning. Median expectations for inflation one year ahead continue to hover near multi-year lows (Figure 10). Businesses, however, are already noting some increase in cost pressures, with the prices paid components of the ISM manufacturing and non-manufacturing indices moving higher this past year. The rise in input costs will place further pressure on business margins and weigh on profitability unless passed on, leading to higher inflation.

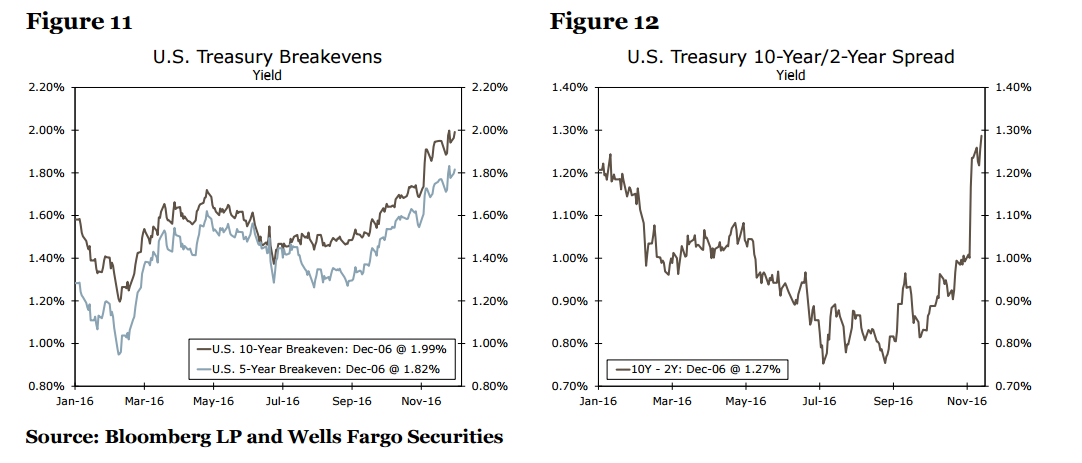

Investors in recent months seem somewhat more cognizant that inflation is once again moving higher. The spread between nominal 5-year Treasury yields and the 5-year yield for Treasury InflationProtected Securities (TIPS) has been rising since September. However, at only 1.80 percent as of this writing, the spread implies investors could still be underestimating inflation; we expect CPI inflation to rise 2.5 percent in 2017, indicating investors risk facing negative real returns at the short end of the curve and smaller real returns at the long end.

Policy Risks Abound in the Coming Year

A number of the policies put forth by President-elect Trump on the campaign trail and in the transition period run the risk of spurring higher inflation, such as greater deficit spending, tariffs on goods from countries “manipulating” their currency and faster credit expansion if Dodd-Frank is cut back. The FOMC currently expects PCE inflation to increase 1.9 percent through the fourth quarter of 2017 and would likely tolerate a modest overshoot before raising interest rates faster than the two hikes currently outlined. That said, in regard to monetary policy, the inflation risk now appears to lie with the FOMC having to raise rates faster than currently discounted rather than a reason to delay normalization, as it has been in recent years.

Moving Toward Where the Puck Is Headed—Not Where it Is Now

Markets move on a deviation from expectations and certainly those expectations were moved by the U.S. presidential election. With Trump as President and a Republican Congress, expectations moved quickly to stronger economic growth, an expectation if not tolerance of higher inflation and a sustained move by the Federal Reserve to follow its dot-plot intentions. These developments support the case for a gradual rise in interest rates from their current levels in the year ahead. Given the one-way movement in financial markets, the feared volatility and flight to safe assets has not transpired, and therefore the concern that the Fed may delay movements has largely dissipated. As illustrated in Figure 11, 5-year and 10-year inflation expectations, measured using TIPS, have drifted up since September and spiked further recently. Meanwhile, the yield curve (10/2-year) has steepened as well (Figure 12). As a result, the Fed is now in a position to follow the market and raise the fed funds rate without the risk of shocking the market, which should result in a flatter yield curve.

Policy and Rates: Always the Fundamentals

For the past two years, given our assessment of the fundamentals of monetary policy, including moderate growth, inflation and significant global capital inflows to the U.S., we have remained below the consensus in our 10-year interest rate outlook and have been well served. For the next two years, the range of possible outcomes is wider given both the size of the market’s reaction already and to the unknown actual policy actions to come.

Our assessment is that economic growth, both real and nominal, will pick up a bit relative to 2016, with the potential for a further boost from a shift in fiscal policy to an expansionary mode. This, along with continued job growth and wage acceleration, should lift consumers’ incomes. Meanwhile, as outlined above, the shifts in actual inflation and inflation expectations are significant and will underpin a higher level of interest rates in 2017 and 2018. The result of these trends solidifies the Fed’s position to raise the funds rate in December and twice in 2017.

Intriguing to watch in the year ahead will be the pattern of global capital flows given the uncertainty around global trade policy and the interaction of investors around the world in response to trade rhetoric. For the past two years, global investors have sought refuge in U.S. dollar denominated agency, corporate and sovereign debt. In recent weeks, capital inflows have boosted the dollar but the target has been U.S. equities and real assets given their sensitivity to stronger real growth and inflation.

Given that interest rates along the yield curve have already moved in recent weeks, what is the direction going forward if investor preferences have already moved to alternative investment forms? How much is already discounted in the marketplace?

Our expectation is that at the short-end of the curve the Fed will follow the current dot-plot projections for 2017. Meanwhile, the long-end of the curve will also move up modestly as inflation expectations are confirmed by rising actual inflation and stronger economic growth and therefore a shift away from risk avoidance buying of Treasury debt toward greater investor interest in corporate debt and equity shares.

Global Outlook/Dollar

Could the Rest of the World Bring Down the U.S. Economy?

The United States is not the only economy in the world that faces uncertainty at present. In this section, we discuss four potential downside risks that are related to foreign economic developments: a debt crisis in China, a return of the sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone, a “hard” Brexit and a trade war. The U.S. economy would feel the effects of foreign economic crises directly via slower growth, if not outright contraction, in exports. In that regard, foreign economic downturns would need to be rather significant to produce a meaningful effect directly on the U.S. economy because real exports are equivalent to only 13 percent of U.S. real GDP. That said, the indirect effects of jittery financial markets that likely would accompany any foreign economic crisis could compound the slowing effect on the U.S. economy.

In terms of upside risks, global economic growth in the next two years could turn out to be stronger than we project if fiscal stimulus in the United States leads to stronger U.S. GDP growth. That said, any positive effect on global growth from U.S. fiscal stimulus likely would be marginal because U.S. GDP is equivalent to about 20 percent of global GDP. For example, a one percentage point increase in U.S. real GDP growth would directly raise global economic growth by only 0.2 percentage points. We also discuss risks and rewards in our outlook for dollar exchange rates in this section.

The Chinese Housing Market Is Looking Frothy While Businesses Are Highly Geared

Chinese economic growth has slowed over the past few years, but the economy has more or less come in for a “soft landing.” Whereas some observers worried earlier this year that growth in China would slow sharply, the GDP growth rate only ticked down from 6.9 percent in 2015 to our projection of 6.6 percent this year. Although we look for further slowing next year—we forecast that real GDP will grow roughly 6 percent in 2017—we are not expecting the Chinese economy to go off the cliff anytime soon. However, the recent sharp rise in house prices, especially in the so-called “Tier-1” cities of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen, raise some concerns about a potential property bubble in China (Figure 13). Could China be looking at a house price meltdown and its attendant consequences such as the United States suffered nearly a decade ago?

Although it may be tempting to draw parallels between the American and Chinese experiences with house prices, the two economies are different in some important ways. First, the household debt-toincome ratio in China at present is 50 percent, well below the comparable ratio of nearly 130 percent in the United States heading into the financial crisis. In short, the average Chinese household simply is not as levered as its American counterpart was a decade ago. Second, residential mortgages represent about 7 percent of the assets of the Chinese financial system at present, less than one-half of the American ratio in 2008 (Figure 14). Everything else equal, Chinese banks would be better positioned to withstand a wave of mortgage write downs, should that transpire, than American banks were at the peak of the U.S. housing market bubble due to less housing market exposure among the former.

However, everything else may not be equal, because Chinese businesses are highly levered with the debt-to-GDP ratio of the nonfinancial corporate sector approaching 170 percent. (The comparable ratio in the United States is 70 percent at present.) Could Chinese banks withstand the double whammy of a burst housing market bubble and a significant increase in the number of non-performing loans in the business sector? Although the Chinese government would have the financial ability to recapitalize the banking system, should the need arise, the rate of economic growth in China could slow sharply before the recapitalization process begins to bear fruit.

Could the European Sovereign Debt Crisis Rear Its Ugly Head Again?

Like the United States and the United Kingdom (discussed further below), many European countries have experienced the rise of populist political forces in recent years. The first round of the French presidential election is scheduled for April 23 with the second round, if necessary, on May 7. Voters in Germany go to the polls a few months later for parliamentary elections in that country. (The exact date of the German election has not yet been announced.) Marie Le Pen, leader of the populist National Front in France, would likely make it to the second round if the French election were held today. In Germany, Chancellor Merkel has seen her approval ratings erode over the past year due, at least in part, to her handling of the refugee crisis.

The future of the Eurozone could be called into question if populist/nationalist political parties, which tend to be skeptical of European integration, do well in these upcoming elections. In that event, the financial market turbulence that accompanied past episodes of the European sovereign debt crisis in 2011, 2012 and again in 2015 could come roaring back. In a worst-case scenario, a break-up of the Eurozone would lead to deep recessions in many European economies. The U.S. economy would not come through unscathed in such a scenario.

“Hard” or “Soft” Brexit?

In a decision that surprised most analysts at the time, British citizens voted to leave the European Union (EU) in the June 23 Brexit referendum. Prime Minister May recently stated that the government will invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty in March 2017, thereby opening the two-year window in which the United Kingdom will negotiate its future economic relationship with the EU. There are many forms that this future relationship could take, and the precise terms are impossible to know at this time. In general, however, a “soft” Brexit would keep in place many of the current terms of the UK-EU relationship while a “hard” Brexit would scrap many of those terms. For example, the future relationship of the UK and the EU could resemble the current US-EU economic relationship. That is, goods, services and people move easily between the US and the EU, although not entirely freely as they do among member countries of the EU.

The United Kingdom is happy with free movement of goods and services but not people because the country wants more control over immigration policy. However, a cornerstone of EU policy is the free movement of goods, services AND people, and it is doubtful that the EU would allow the UK to have the first two privileges without the third. If negotiations start to go badly, investors could fret that a “hard” Brexit, which would entail more adjustment costs for the British economy, is likely. In that event, financial markets could encounter volatility again as they did in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum. That said, the negotiation window should remain open until early 2019, so if this risk materializes it likely will not do so until late 2018, at the earliest.

A Trade War

As a candidate, President-elect Trump was critical of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), vowing to re-negotiate the agreement or perhaps completely withdrawing from it. Movement toward more restrictive trade with Mexico and/or Canada, should it occur, would cause prices of imports into the United States to rise. Higher prices would weigh on growth on American real income, potentially depressing growth in consumer spending. Trump has also stated that he would name China a “currency manipulator.” Such a designation would allow the U.S. government to impose tariffs on Chinese goods, which could lead to retaliation by China. An American trade war with China, should one start, would be damaging to both economies.

The Trump administration likely will not submit the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which was signed by 12 countries including the United States in February 2016, to Congress for ratification. Although non-implementation of TPP would represent an opportunity cost—the trade-enhancing benefits of the accord will not accrue to the economy in coming years—it would not impose direct costs on the economy as would trade restrictions and/or an outright trade war.

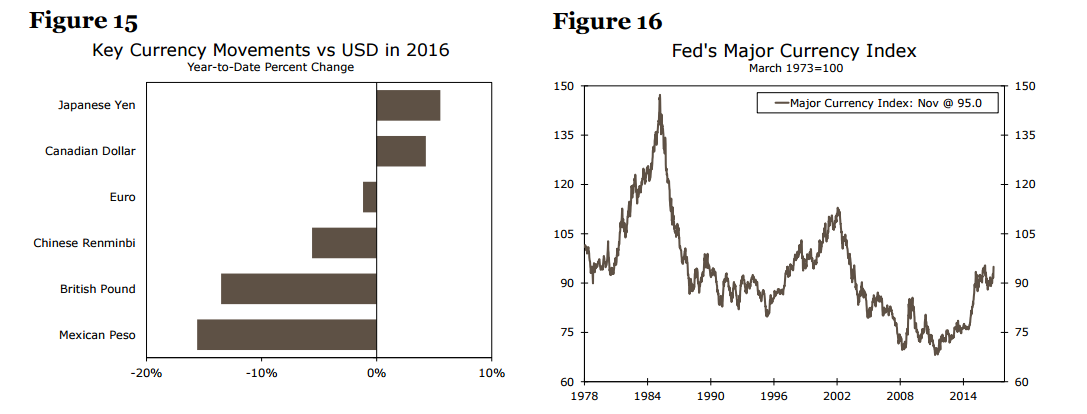

Dollar Outlook: Transition Ahead

For the U.S. dollar, 2016 proved to be a mixed year in part due to global developments and a noticeably cautious approach toward monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve. Early in 2016, concerns about China’s economy were front-and-center for market participants, while around mid-year the U.K. referendum that saw British citizens vote to leave the EU also weighed on financial markets. While the U.S economy showed gradual improvement during the past year, these global events kept the Federal Reserve on the sidelines, and indeed during the periods of greatest market volatility, the timing of an expected Fed rate increase was pushed back well into 2017. While the Federal Reserve now appears to be on course for a December rate increase, these global cross-currents contributed to a rather mixed performance by the greenback. Following weakness for much of the year, after recent gains the Fed’s major currency index is essentially unchanged year-to-date in 2016. The greenback’s performance against individual currencies has been varied. For example, the Japanese yen has gained 6 percent year-to-date against the U.S. dollar in 2016, the euro has fallen around 1 percent and the pound is down 14 percent versus the greenback (Figure 15).

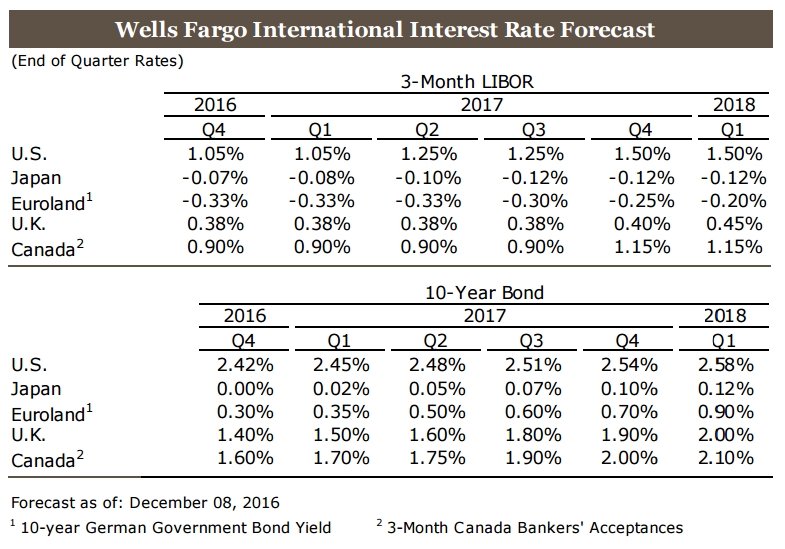

For 2017, we believe a further recovery in the U.S. dollar’s value is probable. We expect the U.S. dollar to strengthen surrounding a likely December Fed rate hike, and although some U.S. dollar consolidation is possible early next year, we see overall U.S. dollar strength in 2017. While we do not forecast an especially rapid pace of Fed tightening, we do see some pick-up from the pace of tightening in 2015 and 2016 and, moreover, we expect the Fed will move faster than is currently implied by the interest rate futures curve.

As a result, we anticipate some further divergence between U.S. and global monetary policy, and thus U.S. dollar strength in 2017. The prospects for renewed monetary policy convergence in our opinion does not so much hinge on Fed policy, but rather on a less dovish/more hawkish shift in policy stance or bias from other important central banks. Assessing the international landscape, such a shift in a less dovish direction does not appear likely in the near-term, although the European Central Bank and/or the Bank of Canada perhaps offer the best prospects for such a shift in policy in the medium-term, which could eventually dampen the greenback’s performance. As a result, we believe a turn in the U.S. dollar’s longer-term cycle, from appreciation to depreciation, is more likely to occur in 2018 than in 2017. Should the Fed’s major currency index appreciate as we expect over the next year or so, then by late 2017/early 2018, the greenback’s long-term up-cycle will have lasted around 6.5 years and seen an appreciation of approximately 45 percent, a length and magnitude that is historically consistent with the U.S. dollar’s broader long-term cycles (Figure 16). Against this backdrop and in the context of what is an aging U.S. economic cycle, we are also aware that the U.S. dollar’s appreciation is getting mature, and increasingly we will be looking for signs of a turn in the foreign exchange market cycle.

To sum up, while we do not believe the U.S. dollar’s appreciation cycle is over yet, we do believe it is nearing its end. In early 2017, we believe the risk/reward trade-off favors planning for a stronger U.S. dollar, but by early 2018 we think the risk/reward trade-off could favor planning for a weaker U.S. dollar. Meanwhile the timing of U.S. and global monetary policy moves remains the key risk around the U.S. dollar’s exact path. Faster than expected Fed tightening, potentially related to more expansive fiscal policy, could see a more rapid U.S. dollar appreciation than we currently forecast. Should some of the global risks referred to above transpire, the U.S. monetary policy outlook could move in a less hawkish/more dovish direction, but so too could the global monetary policy outlook. In addition, global financial market strains could weigh on emerging currencies in this scenario. Thus even if global economic and financial market performance disappoints to the downside, we would still expect some moderate U.S. dollar gains in 2017.

20161208