Holograms

Holography is the science and practice of making holograms. Typically, a hologram is a photographic recording of a light field, rather than of an image formed by a lens, and it is used to display a fully three-dimensional image of the holographed subject, which is seen without the aid of special glasses or other intermediate optics. The hologram itself is not an image and it is usually unintelligible when viewed under diffuse ambient light. It is an encoding of the light field as an interference pattern of seemingly random variations in the opacity, density, or surface profile of the photographic medium. When suitably lit, the interference pattern diffracts the light into a reproduction of the original light field and the objects that were in it appear to still be there, exhibiting visual depth cues such as parallax and perspective that change realistically with any change in the relative position of the observer.

In its pure form, holography requires the use of laser light for illuminating the subject and for viewing the finished hologram. In a side-by-side comparison under optimal conditions, a holographic image is visually indistinguishable from the actual subject, if the hologram and the subject are lit just as they were at the time of recording. A microscopic level of detail throughout the recorded volume of space can be reproduced. In common practice, however, major image quality compromises are made to eliminate the need for laser illumination when viewing the hologram, and sometimes, to the extent possible, also when making it. Holographic portraiture often resorts to a non-holographic intermediate imaging procedure, to avoid the hazardous high-powered pulsed lasers otherwise needed to optically “freeze” living subjects as perfectly as the extremely motion-intolerant holographic recording process requires. Holograms can now also be entirely computer-generated to show objects or scenes that never existed.

Holography is distinct from lenticular and other earlier autostereoscopic 3D display technologies, which can produce superficially similar results but are based on conventional lens imaging. Stage illusions such as Pepper’s Ghost and other unusual, baffling, or seemingly magical images are also often incorrectly called holograms.

How do you make a hologram?

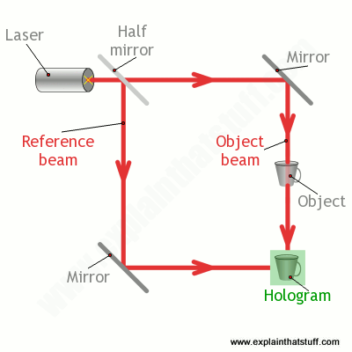

You make a hologram by reflecting a laser beam off the object you want to capture. In fact, you split the laser beam into two separate halves by shining it through a half-mirror (a piece of glass coated with a thin layer of silver so half the laser light is reflected and half passes through—sometimes called a semi-silvered mirror). One half of the beam bounces off a mirror, hits the object, and reflects onto the photographic plate inside which the hologram will be created. This is called the object beam. The other half of the beam bounces off another mirror and hits the same photographic plate. This is called the reference beam. A hologram forms where the two beams meet up in the plate.

How holograms work

Laser light is much purer than the ordinary light in a torch beam. In a torch beam, all the light waves are random and jumbled up. Light in a torch beam runs along any old how, like schoolchildren racing down a corridor when the bell goes for home time. But in a laser, the light waves are coherent: they all travel precisely in step, like soldiers marching on parade.

When a laser beam is split up to make a hologram, the light waves in the two parts of the beam are traveling in identical ways. When they recombine in the photographic plate, the object beam has traveled via a slightly different path and its light rays have been disturbed by reflecting off the outer surface of the object. Since the beams were originally joined together and perfectly in step, recombining the beams shows how the light rays in the object beam have been changed compared to the reference beam. In other words, by joining the two beams back together and comparing them, you can see how the object changes light rays falling onto it—and that’s simply another way of saying “what the object looks like.” This information is burned permanently into the photographic plate by the laser beams. So a hologram is effectively a permanent record of what something looks like seen from any angle.

Now this is the clever part. Every point in a hologram catches light waves that travel from every point in the object. That means wherever you look at a hologram you see exactly how light would have arrived at that point if you’d been looking at the real object. So, as you move your head around, the holographic image appears to change just as the image of a real object changes. And that’s why holograms appear to be three-dimensional. Also, and this is really neat, if you break a hologram into tiny pieces, you can still see the entire object in any of the pieces: smash a glass hologram of a cup into bits and you can still see the entire cup in any of the bits! (You can see a demonstration in this great video of cutting up a hologram and Hyperphysics has a more detailed explanation of exactly what we mean when we say “a piece of a hologram contains the whole object”.)